Zebrafish Embryos Expose Cisplatin's Kidney Damage Pathway

March 11, 2025

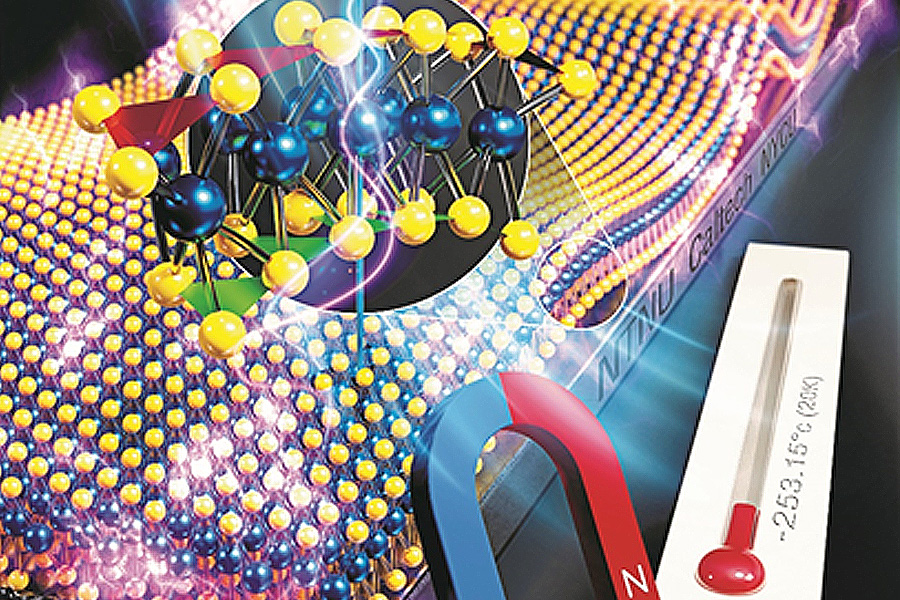

Traditional animal experiments often rely on mice and rabbits, but they often spark ethical controversy. Distinguished Professor Li-Yih Lin of the Department of Life Science at National Taiwan Normal University leads a research team that makes effective use of a zebrafish embryo model to successfully elucidate the nephrotoxic mechanism of the chemotherapeutic drug, cisplatin. This work has not only opened up a new direction for developing protective drugs that counter nephrotoxicity, but also highlights the innovative value of alternatives to conventional laboratory animals, which is aligned with international standards that increasingly emphasize animal welfare. Professor Lin specializes in fish environmental physiology and toxicology, and his laboratory focuses on how harmful substances in the environment affect aquatic organisms. Early on, the team studied how fish embryos adapt to global warming and aquatic acidification. During that process, they discovered that ionocytes on the skin of zebrafish embryos regulate acid–base balance and ion uptake, and that their function is highly similar to that of human kidney cells. This finding prompted the research to extend into medical applications. Collaborating with clinicians, the team found that widely used chemotherapy drugs such as cisplatin, while highly effective against cancer, can cause nephrotoxicity in patients and lead to impaired kidney function. In addition, if medical wastewater containing cisplatin or patients’ excreta enters natural water bodies, it may also harm aquatic organisms such as fish. To address these issues, the team used zebrafish embryos, the cells of which share some functional similarities with human kidney cells, as a model to test whether antioxidant drugs can reduce cisplatin-induced cellular injury. The results showed that antioxidant drugs can indeed reduce oxidative stress and lower the cell death rate. These findings not only strengthen the work’s clinical reference value, but also provide new possibilities for developing protective drugs against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Figure caption: Zebrafish embryonic ionocytes are mitochondrion-rich cells with functions similar to those of human kidney cells. Under the action of cisplatin, mitochondria within the cells are damaged, reactive oxygen species (ROS) increase, and apoptosis is triggered. However, unlike traditional studies that use mice and rabbits as experimental animals, zebrafish embryos come with fewer ready-made techniques and pieces of equipment. Professor Lin notes that the biggest challenge in this study was how to rapidly detect drug-induced damage and changes in cellular function in these tiny embryos. To overcome this, the team developed a non-invasive scanning ion-selective electrode technique to precisely measure ionocyte function, and introduced multiple fluorescent staining methods to rapidly detect mitochondrial injury and oxidative stress in ionocytes. These breakthroughs enabled the team to quickly characterize how chemotherapy drugs affect ionocytes. This research not only contributes to clinical medicine, but also offers a new perspective on animal experimentation. Professor Lin explains that because the nervous system of zebrafish embryos is not yet fully developed, their capacity to perceive pain is limited. Their transparency also allows researchers to reduce the need for invasive procedures. In particular, zebrafish embryos can be used across multiple toxicity research areas, including nephrotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and neurotoxicity, which can effectively reduce reliance on traditional animal experiments, meet international animal welfare expectations, and provide an efficient, ethical, and reliable alternative. Looking ahead, Professor Lin says the team will further optimize the zebrafish embryo toxicity testing system to cover additional toxicity categories such as cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and ototoxicity. By improving analytical methods and refining the platform, they hope to more accurately model how human cells respond to drugs, thereby reducing the need for higher animals such as mice and rabbits in the early stages of drug development. This approach not only meets humane goals, but also improves the efficiency and reliability of toxicity testing while reducing the costs and ethical disputes associated with traditional animal experiments. Professor Lin emphasizes that the techniques and methods developed by the team are not limited to chemotherapy drugs. They can be broadly applied to toxicity testing for many kinds of pharmaceuticals: any drug that may damage mitochondria or induce oxidative stress can be evaluated using this approach. At the same time, zebrafish embryos are also an ideal alternative model for international chemical toxicity testing. This research not only advances more humane experimental practices, but also supports national policies promoting alternatives to animal experimentation, offering a practical and innovative model for reducing animal use. (This article was provided by The Center of Public Affairs.) Source: Hung, G. Y., Wu, C. L., Motoyama, C., Horng, J. L., & Lin, L. Y. (2022). Zebrafish embryos as an in vivo model to investigate cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in mitochondrion-rich ionocytes. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part - C: Toxicology and Pharmacology,259, Article 109395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2022.109395